I’ve got a little bit obsessed recently with a particular Chopin Prelude recently, and it seems that a lot of people have done so before me. Op. 28 No. 20 has inspired sets of variations, jazz covers, and even pop songs.

It has also been used frequently in piano pedagogy, probably for its superficial simplicity, combined with the near-limitless technical challenges it can offer. One notable teacher who used the piece a lot if you look at his lesson books, was Heinrich Schenker (subtle foreshadowing).

Looking through my copy of the Préludes, and after spending a long time trying to get the melody to come out, I played this:

It’s far from perfect - my left hand is a little heavy, and my pianissimo isn’t quite issimo, but it’s amazing how much it forces you to think about the balance of the right hand, as well as building phrases.

Since starting to play it, I’ve become obsessed with every little detail of these thirteen bars and how they work. I think it’s particularly interesting to analyse tiny little pieces of music like this - you can really grasp every little detail and understand how it works. For that reason, this is going to become a deep dive, and some of it will be very technical. It’s my aim to try and explain some of those technical elements, so stay with me if you dare!

Préludes Op. 28

The obvious question is: preludes to what? The set of 24 preludes was written between 1835 and 1839. There are 24 in different keys in tonal music (major and minor for each of the key centres), and the idea of writing a set of keyboard pieces in every key is more than likely inspired by J. S. Bach’s two sets of 24 preludes and fugues, arranged methodically starting in C major, then C minor, then C♯ major, etc. These preludes are essentially free compositions, some of them potentially originating as improvisations, which pair with the more formal contrapuntal fugues. Chopin leaves the fugues in the eighteenth century where they belong (sorry fugue fans) and arranged the keys in a more natural order in terms of related keys, following the pattern of C major, A minor, G major, E minor, etc. They’re tiny little pieces and range from easy to play to extremely virtuosic. Franz Liszt described them as “poetic preludes, analogous to those of a great contemporary poet, who cradles the soul in golden dreams.”

The Prelude on the Surface

A couple of notation things:

Number preceded by a caret (^1, ^2, ^3, etc.) - Scale degrees in relation to the key. So ^5 in C minor is the fifth of the C minor scale, which is G.

Numbers without the caret will normally be in relation to the bass - for example, if I talk about a 7-6 suspension, I am referring to a note 7 steps above the bass note followed by the note 6 steps above the bass.

Roman numerals refer to the harmony and tonality. I primarily will not follow the convention of upper case for major and lower case for minor, but instead use figured bass and accidentals in relation to the key.

But first, a bar-to-bar commentary:

The whole prelude has a consistent rhythm - Bum-bum-bum-di-bum. It gives the whole thing a serious, heavy feel.

Bar 1: The melody starts on ^5, embellished by going up to ^6 and back down (an auxiliary note). This is a move familiar from another famous minor-key Chopin Prelude - No. 4 in E minor. The melody then passes through ^5-^4-^3. Meanwhile, the harmony goes through I-IV-V♮-I. The harmony of the V chord includes a b6-5 movement, which you could describe as a consonant suspension - as we will discover when we get deeper, this is a surface level extrapolation on a broader structural foundation.

Bar 2: The melody and the bass follow in sequence, briefly tonicizing VI (A♭ major).

Bars 3-4: The previous bars have been phrases in themselves, but bar 3 begins a two-bar phrase, rising through chromatic notes. Although the phrase as a whole rises, each part descends. It is like each part of the phrase is climbing a ladder. Meanwhile, the harmony moves towards tonicizing V, though the fact that we land on a major V primes the ear to land back in the key of C in bar 5.

Bar 5-6: In bar 5 we begin a four-bar phrase, the first two bars of this feature a “lament bass” - a stepwise descent (in this case chromatic) from the tonic (I) to the dominant (V). If the associations with tragedy (perhaps most famously with Dido’s Lament) weren’t enough, the top line, starting on ^3 is also descends in tenths, meanwhile a middle line (which I will argue is actually the melody), goes from ^5 to ^6, as at the beginning, which prepares two 7-6 suspensions. To explain this, in beat 3 of bar 5, the middle line is on Ab, a (dissonant) diminished 7th above the B♮, before falling to a (consonant) major 6th above the B♭ in the bass (with an additional F♯ decoration in between). Bar 6 also continues with a 7-6 leading to a very exciting French Augmented Sixth. I’m going to take a quick sidebar to explain that.

Augmented Sixth Chords

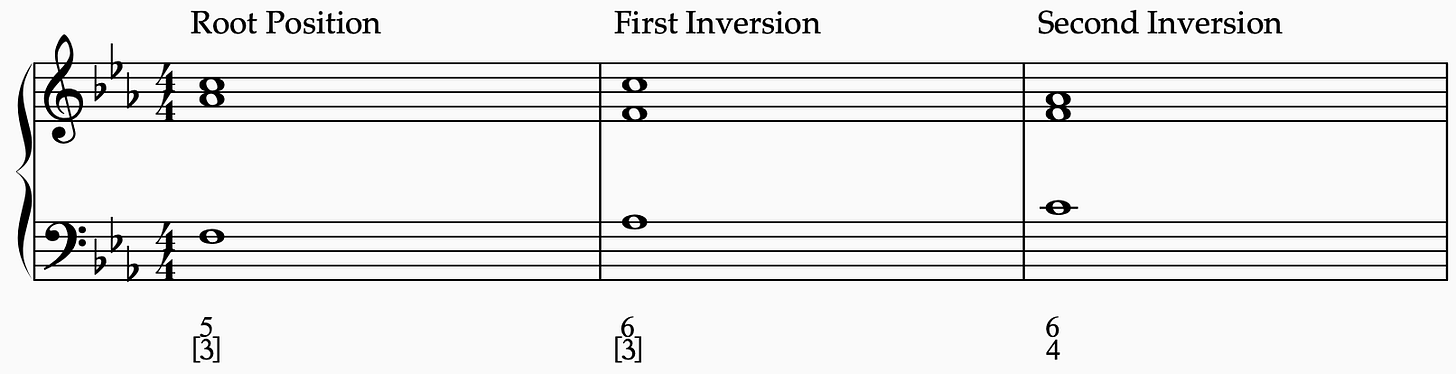

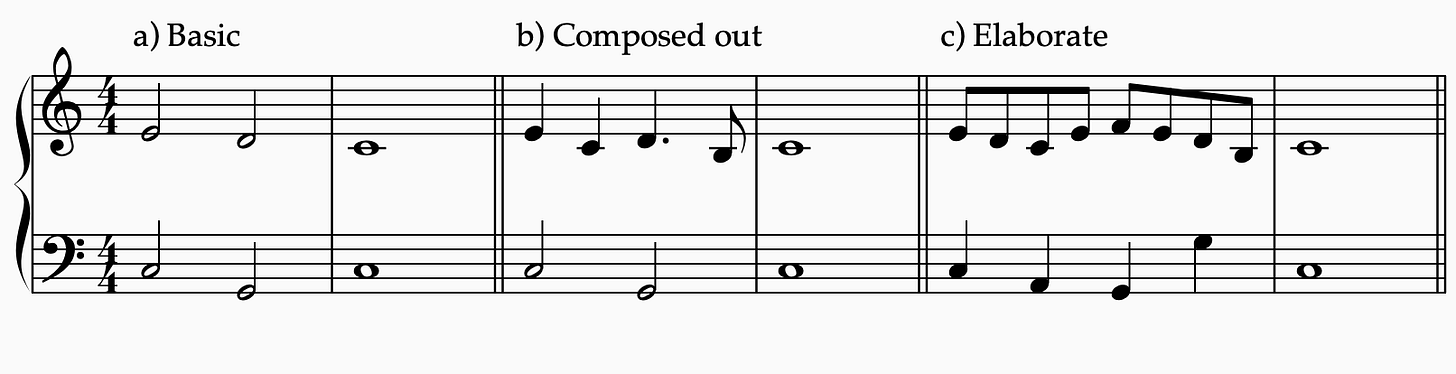

There are few more poorly explained concepts in music theory than Augmented Sixth Chords. I’m not going to go on about them being like dominant chords, because they’re not. An Augmented Sixth Chord is essentially an altered chord IV in first inversion - that just means the third of the chord is in the bass.

Chord IV in first inversion is a common pre-dominant chord - that is a chord that precedes chord V, which in turn leads to the tonic chord of the home key.

Back in J.S. Bach’s day, a first inversion chord was notated with the number 6, because that is the interval between the lowest sounding note and the root note of the chord. In a minor key, that will be a major sixth. At some point, composers discovered that you can intensify this movement by raising the root note of the chord, in turn “augmenting” the size of this interval to the titular augmented sixth, which then resolves outwards by semitone to an octave on chord V.

The basic version of this is called the Italian Sixth. This chord can be embellished further by either a fourth or a fifth to give the French or German Sixth.

In short, the Augmented Sixth chord is nothing but a special case of a chromatically altered note that intensifies the drive of a pre-dominant chord towards the dominant.

Back to the analysis

Bar 6: When the music gets to chord V, the harmony does not rest there, with the bass passing through the seventh to a first inversion tonic chord at the beginning of bar 7.

Bar 7-8: The melody of the first two bars repeats, but now reharmonized to land safely in C minor. This time the 6-5 motion over chord V reappears, but this time as the main melody.

Bar 9-12: A repeat of 5-8, even quieter, but getting louder at the end. This was not in the earliest drafts of the Prelude, and part of my analysis will address why it was added.

Bar 13: A final, key-affirming chord.

Getting Deeper: A Note on Schenkerian Analysis

Often when we analyse a piece of music, we have a tendency to stop after spotting these features. When we did our GCSEs, you were expected to spot all the features and stop there. This proves a music-theoretical toolkit and an attention to detail, but does little to understand why certain decisions were made and not others.

To investigate this, I will employ techniques from Schenkerian Analysis. Now, I should say that Schenkerian Analysis is at the centre of what amounts to a culture war in the field of music theory, with pretty much everyone (apart from a few conservative holdouts) agreeing that the man after whom the field is named, Heinrich Schenker, was a horrible racist. The big disagreement between the more reasonable minds is over whether Schenker’s racism has a direct bearing of his theories of music, and those of his followers, or whether the techniques of analysis that he developed can reasonably be used in a way that is not racist. If you’re interested, I’ll direct you to Philip Ewell’s article that brought the question into (but music theory standards) mainstream discourse and an interesting rebuttal by Bryan J Pankhurst.

My personal view is that Schenker developed a very insightful approach to understanding the procedures of tonality in a particular limited repertoire, and then declared that anything that didn’t follow this procedure was incorrect and bad. Since then, theorists have expanded the applicability of his work, and with a few exceptions, have broadly eschewed considering it as the criterion for “greatness”. That’s why I use it - Ewell, even in his strongest condemnations actually doesn’t say it’s inherently wrong to use Schenkerian analysis, and mostly suggests it should be optional (which, in the UK, it is - I was lucky to even have the option of studying it under Nick Marston in my second year of university). It does provide insights into the music Chopin (who is the rare non-German inclusion in Schenker’s canon), it’s just important to be a little bit careful whenever you use it.

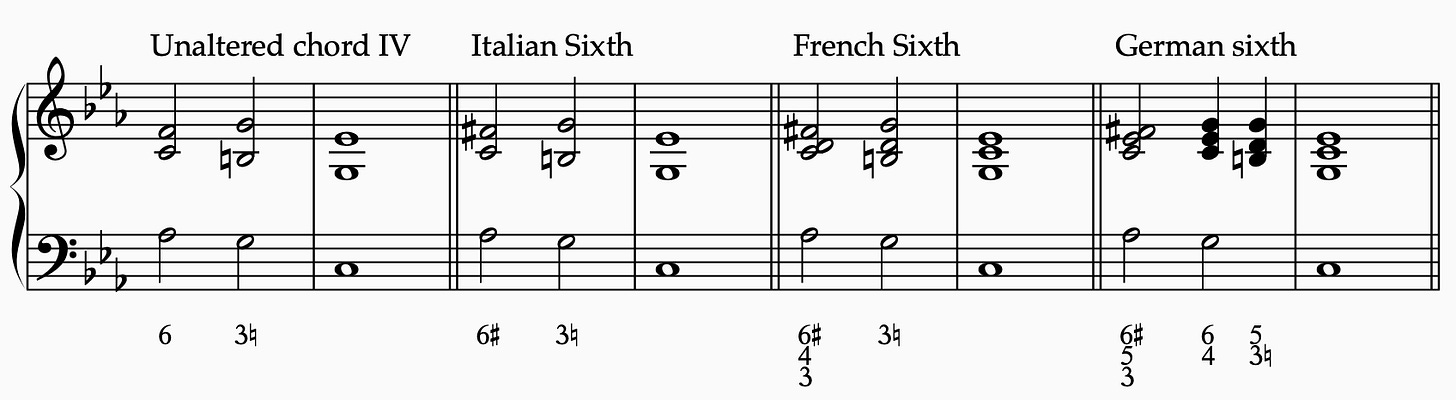

With that said, the foundation of Schenkerian Analysis is the claim that a piece of tonal music is an elaboration on a fundamental background structure. You know how when a singer riffs around a melody but (if they do it well) it’s still the same melody you know? The contention essentially takes that and puts it to the extreme. The melody itself is a riff (or to be more precise a “composing-out”) of some more fundamental background. As some levels of analysis, this is trivially true. Take the following example of how a simple melody can be expanded through passing notes and other added notes, while still retaining its core identity.

The bolder Schenkerian claim is that in a certain repertoire of tonal music, this is expanded out into a whole movement of music through successive layers of expansion.

The most common of the background structures is the one you see above: ^3-^2-^1 in the melody, accompanied by I-V-I in the bass. The second most common is the one which this prelude uses, beginning on the ^5.

My Analysis

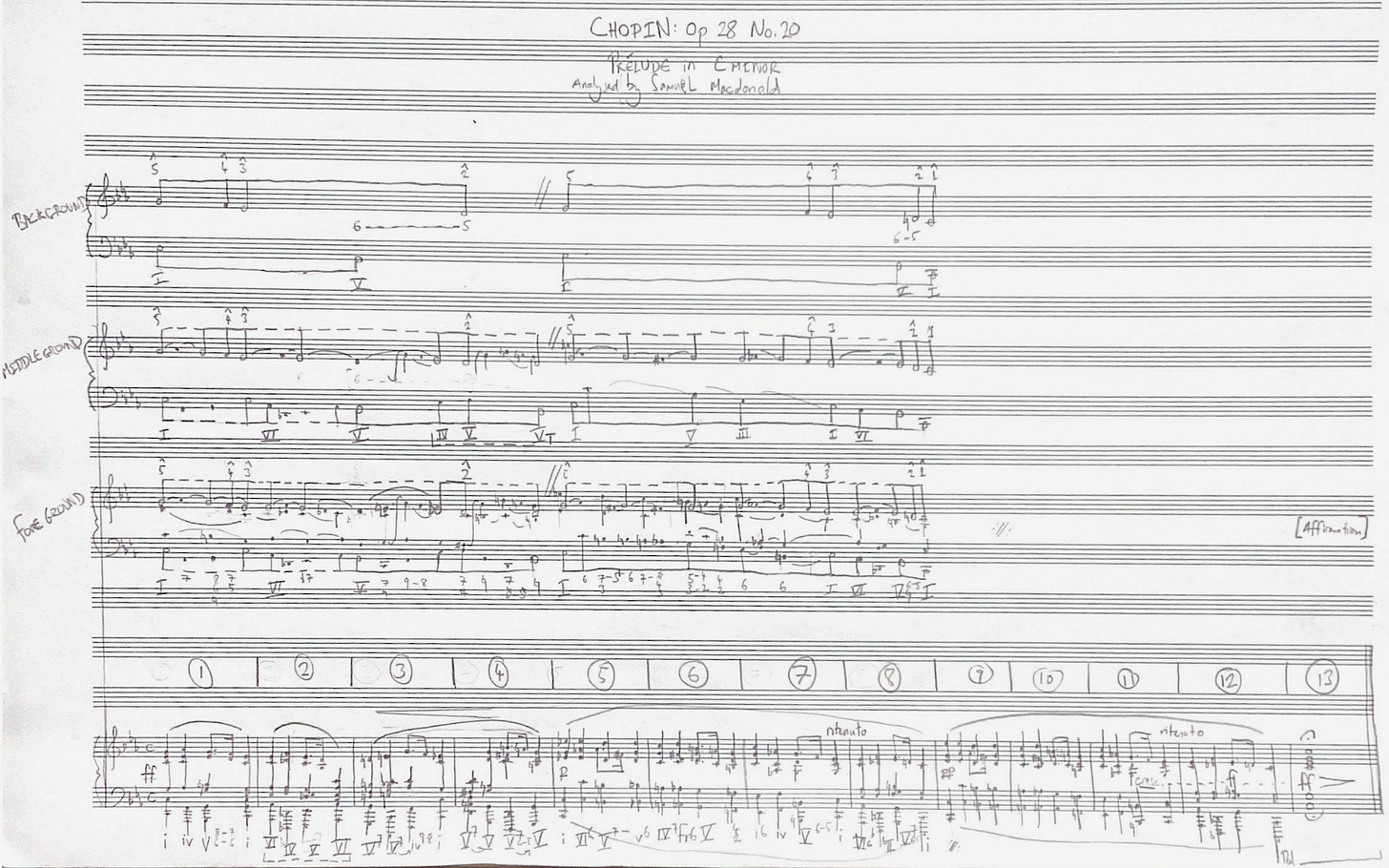

Let me explain what this monstrosity is. The top two staves show what I claim to be the background structure of. In Schenkerian Analysis you give empty noteheads to notes of structural importance, and filled noteheads to notes of less structural importance. The ^4 in the background line is filled in because in the background, it acts as a passing note. The tramlines in the centre of the score indicate an “interruption”. This is effectively when the fundamental structure “fails” to resolve, instead landing on ^2 and the music starts again at the beginning of the fundamental structure to finally resolve on ^1 (this is the foundation of a periodic structure and, on a larger scale, sonata form).

Even though this is a fundamental structure, there is something individual to this background which we will see extrapolates into further structural levels, and that is the misalignment between the V in the bass and the move ^3-^2. This produces the 6-5 consonant suspension that appears beat 3 of bar one and various other places on the surface of the piece. It’s interesting to see it also at the background. There is a potential reading where this doesn’t happen, but I’ll have to justify my reading at the next structural level - it leads to parallel fifths, which are a no-no.

Next we have the middleground, where we start to see auxiliary notes. Both the obvious ones, like the A♭ in bar 1, and the less obvious ones. In particular there is a contentious choice of which tones are structural and which are auxiliary over the structural V. The line at the middleground level goes ^3-^2-^3-^2. The question is: do we remain in structural ^3 and the first ^2 is an auxiliary note, or do we go into structural ^2 and the second ^3 is a auxiliary to that? There are a couple of reasons why I opted for the former. The main one is that at this structural level, moving from ^3-^2 would make a parallel fifth with the VI-V in the bass. Subjectively, too, the ^2 sounds like it has an upwards momentum, especially with the ^♯3 that follows it. It is interesting the impact that this reading has on an ambiguity in the sources for this prelude. A significant Dover edition, and one of Chopins autograph scores has an E♮ on beat 4 of bar 3 (or rather the note has no accidental, which means it takes on the E♮ from earlier in the bar), but other Chopin autographs make it a clear E♭. The clincher for me is that there are a few sources where Chopin has written in the ♭ into a pupil’s book, but even so, some (especially older) performances go for the E♮. My reading here relies on the E♭, so it is important!

Once we reach ^2 it remains until the interruption, but an inner voice reaches over creating what is called a “cover tone”, when an inner voice reaches over the fundamental line - this is what creates the feeling of the phrases climbing the ladder in bar 4. After the interruption, we still have a cover tone, and the main melody is actually in the inner voice. The Schenkerian arguments for this are two-fold. One is that we expect to go back to ^5 after the initial descent fails, and the second is that the covering voice drops out when we reach beat 2 of bar 7 and we see the was the rise from G to A♭ mirrors the initial auxiliary note. There are surface level elements that justify this too. In particular, in bar 5, it is only this inner voice that continues the pervasive dotted rhythm of the piece on A♭-F♯. When we appreciate this fact, we can see how on some level the second four bars is a near repeat of the first four, with the ^5 area expanded through an unfolding of a tonic triad in the bass.

The foreground aims to show the details of how we bridge the gap between these structural levels and the final piece - most of which I covered in the initial commentary.

You’ll notice that the graphs stop abruptly when we get to bar 9. That’s because, from a purely tonal Schenkerian perspective, bars 9-13 are technically superfluous. We have already reached tonal closure, and though it is not uncommon in tonal music to repeat the tonal closure, it is not strictly necessary. In fact this is borne out by the fact that early drafts did not include bars 9-12. But Chopin did decide to add them, so the fascinating question becomes: why?

Tonality and Rhetoric

As much as it’s interesting and insightful to peel back the layers of a piece like this, noone makes music to resolve a tonal argument. The genius of this music is that it uses the tonal argument to make a truly heart-rending expressive piece of music. There are a whole host of reasons why repeating this section helps that: the dimensions of the piece now favour the lament bass, so this descent is emphasised. With the tonal argument already stated once, the listener can enjoy it the second time hearing the inevitability of what’s about the happen. Meanwhile, the repeat has extreme dynamics, from the intense pianissimo to the fortissimo at the end. If we’re to imagine a character experiencing emotions, we could imagine them trying to hold themselves in until everything bursts out at the end. Finally, the repeat just allows us to sit in the music for a little longer, and enjoy it.

All these reasons (and I’m sure there are more) are important reminders that music is not just about achieving the task of getting a piece done. It doesn’t outstay its welcome by, but it does more than “get in and get out”, which I admit is often my motto in writing music, particularly for theatre. It’s a useful rule of thumb to remind you to be economical with material, but sometimes it’s right to indulge the music just a little more, and squeeze out every ounce of emotion from the idea.

Conclusions

There is so much depth to be uncovered even in a tiny little piece of music like this, but it’s not unique to Chopin. I seem to be in a period where I’m wanting to write stuff for this blog at the moment, so maybe I’ll do this for some musical theatre songs? Some of them can be just as complex as this and we don’t often get to proper grips with it. So I guess… follow for more?

My life would have been so much easier so much earlier if someone had explained Aug6 chords to me they way you just did 🧠